Chasing trains at midnight, running through ditches at dawn, tromping around a condemned warehouse in the dead of night. These aren’t the most romantic places to go on a date for most Memphians, but for Neen and Barl, two talented graffiti writers, it’s not the location that matters, but the collaboration, the sharing, and the competition that drives them. These two have each other’s back, while they develop a relationship that shows their passion for the other and for their public art.

Chasing trains at midnight, running through ditches at dawn, tromping around a condemned warehouse in the dead of night. These aren’t the most romantic places to go on a date for most Memphians, but for Neen and Barl, two talented graffiti writers, it’s not the location that matters, but the collaboration, the sharing, and the competition that drives them. These two have each other’s back, while they develop a relationship that shows their passion for the other and for their public art.

Though both Neen and Barl have had a talent for art since childhood, they came to graffiti “late,” in college while studying fine art. Barl’s first real introduction was in orientation freshman year, where he sat, wearing a Banksy t-shirt, across the table from Rakn, who hails from Kansas City. Rakn noticed the shirt straight away, and the two became fast friends and quick graff writers. “At this point, I was still a complete toy and Banksy was my hero,” Barl says. “We started talking about graffiti and he pretty much made my head explode.” Rakn and Goes, another local writer, showed Barl locations and techniques, and, of course, Barl took Neen along.

Neen caught on faster than anyone expected, proving that she could easily transfer her training as a traditional painter into a prolific and well-crafted graffiti writer. “Spray cans were no different from paint brushes. It was just going from 12″ x 6″ paper to an entire freaking wall that was so foreign. For me, the idea of spray cans was really no less exciting than the invention of tubed paint for eighteenth century artists. Instead of paint brushes, you have caps. All you have to do is shake and control it (and watch your back).” She impressed Barl and other, more experienced writers bombing with them like Rakn, Goes, and Toby her first few times out. She seemed a natural, moving from paint brush to spray can competently.

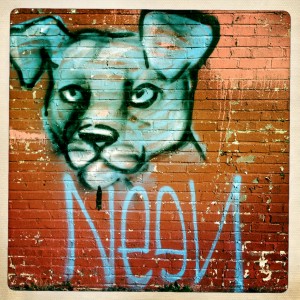

So Barl watched her back and the two start collaborating, using complementing colors and images to link them. First they started tagging, quick, one-color names on as many locations as possible, but soon realized that it was both dangerous and not as aesthetically appealing to them as art was. So they pulled from their childhoods, their interests, and their studies, and found a place within sequential narratives, or comic books and graphic novels, in which they could combine their knowledge of illustration and painting and translate it into public graffiti pieces. They cite international comic artists and illustrators as their greatest influences: Brazilian Rafael Albuquerque, Americans Sean Murphy and Alex Pardee, and German Marko Djurdjevic, for their use of color, lines, and space. But Barl also gives a nod to horror films, heavy metal music, and even Yu-Gi-Oh. Neen’s figures, who are mostly women, are reminiscent of Rodolphe Guenoden’s strong and sexy superhero types of ladies, she says, with sexy cat or sweet puppy on rare occasion. And she can certainly do a fine Sailor Moon when the surface or situation begs for it.

They learned quickly that by working together they could take their time, plan their pieces, do more than just tag or throw up their names. They could transform their environment. For Barl, it’s a matter of combating commercialization with public art: “We are constantly barraged by an uncountable number of advertisements. The corporations and marketing agencie who put these ads out never ask the residents if it’s okay to make their environment all commercialized; they just do it. So it is only fair for the inhabitants to put out something that people may actually want to look at, or at least something to make things more interesting.” And, as with all graffiti writers, it’s a matter of excitement. Barl adds, “It provides a chance to break out of the monotony of everyday life to go on an adventure. Who doesn’t love an adventure?”

For Neen, it gives her a chance to try, and succeed, at a new medium, one that took her out of her house and made her art  mobile and much more accessible to a wider audience. But she realizes the bigger implications and dangers of graffiti. “It’s easy to jump in and commit, but what so many kids don’t realize is the literal and metaphoric price that comes with it. Spray paint can be expensive, and so many of graffiti artists steal in order to pursue what they love. The metaphoric cost is your reputation, your parents’ well-being (my momma worries enough as it is), your future, and also your moral code.” She and Barl are in it “for the art,” not for the pursuit of getting their name known, and certainly not to be known as thieves.

mobile and much more accessible to a wider audience. But she realizes the bigger implications and dangers of graffiti. “It’s easy to jump in and commit, but what so many kids don’t realize is the literal and metaphoric price that comes with it. Spray paint can be expensive, and so many of graffiti artists steal in order to pursue what they love. The metaphoric cost is your reputation, your parents’ well-being (my momma worries enough as it is), your future, and also your moral code.” She and Barl are in it “for the art,” not for the pursuit of getting their name known, and certainly not to be known as thieves.

In addition, the quality of their work improves as they plan their pieces and find their spots together. The two often paint trains, as railroads give their work a moving canvas that can travel all over the US, displaying their art to people who may never come to Memphis. Passing on overpasses in big cities, through the middle of small towns and even corn fields, the train act as a traveling art show, featuring the works of lots of graffiti writers who often don’t even know each other. The limitations of scope and scheme are boundless in graffiti. Barl believes, “Graffiti, more than any other visual art form, has the most room for innovation, yet not many people have any desire to realize the potential of this medium. I want to make stuff that no one has seen before, stuff that only I can make. Before you can do this, you have to have a fundamental understanding of the medium, and a good amount of can control. But after you have that down, there is absolutely no limit to what you can do.”

But they also like to take their time and paint in legal spaces or abandoned building and ditches, where they can focus more on their craft instead of the railroad “bulls” or police chasing them down. In these less public areas, they still create separate images, that mirror their individual styles, but the works get larger and the messages make more impact when they collaborate. Neen may do one character in her softer, more colorful mode; while Barl has a corresponding character using his own graphic, darker style. And in the middle of making art, their relationship grows.

Barl’s work often warrants Neen’s appreciation. “It’s awesome turning a mission into a date,” he says. “However, there is a big aspect of competition in our relationship. I always know that I painted a good piece whenever she comes over and punches me in the arm.” Like many graffiti writers, they are inspired by holidays, but in their case it’s Valentine’s Day or their anniversary. Barl comments, “At one point we did this collaboration in memory of our rat who died, Trippy Walter. I painted a rat god with a scepter standing upright, while Neen painted Trippy being crowned by the rat god. Under it she wrote, ‘Now with the Rat Gods.’” Neen has a greater understanding of the coupling of danger and intimacy in their collaboration: “It’s great working with someone you’re really close with in dangerous situations where you have to be quiet; because our frequencies are always tuned together, we don’t have to speak much.”

The two will continue to paint together, trying to make the world around them a more beautiful place through their graffit and fine art. Granted, that includes Barl’s skull-like heads throwing up his name butting right up next to Neen’s sexy cat crawling out of a blue background. Most Memphians will be lucky to catch a glimpse of these treasures that lurk in little known ditches and abandoned buildings. But if you stand at Sun Studio and look up at the back of the billboard over Domino’s pizza, you’ll see a heaven piece that Barl and Neen worked on with Rakn. To that extent, everyone is lucky in terms of graffiti: lucky to avoid the cops and death while working, lucky to see works that are hidden right in front of our eyes, and lucky to work together to create some of the best, cutting-edge art with someone they adore. So, in chasing trains, they chase the luck, and each other in the process. Let’s hope they keep painting along the way.

By Karen B. Golightly